Anxiety Disorders Are Emotional Older Adults Peer Reviewed Journal

Emotional noesis involves a range of functions, including 'perceiving, interpreting, managing, and generating responses to socially relevant stimuli, such every bit intentions and behaviour of others'. Reference Green, Hellemann, Horan, Lee and Wynnone Being able to undertake these functions efficiently is an important part of interpersonal relationships and social interactions. Interpretation of affective information is vital to these interactions as information technology influences emotional states and governs behavioural responses in social situations. Difficulties in social situations and avoidance of these, in the context of mental disorders, may maintain clinical levels of distress in patients and hinder attempts to treat their disorder. Further, emotional material can impair efficient cognitive processing past inducing biases in attention or determination-making, and by interfering with efficient cognitive processing, thereby impairing other aspects of cognition.

Emotion Processing in Low

The cognitive neuropsychological hypothesis of low Reference Warren, Pringle and Harmer2 posits that in low there is both behavioural and neurocircuitry testify of a bias toward negative emotional stimuli. It is suggested that those who are more vulnerable to depression tend to perceive social cues as more negative and nourish to, and recall more than, negative information. Reference Disner, Beevers, Haigh and Beckiii These biases may play a role in precipitating depression, maintaining low and conferring susceptibility to relapse. Antidepressants may reverse this bias relatively quickly, but it takes some time for this change to be translated, via improved social interactions, into a reduction in depressive symptoms. Reference Harmer, Bhagwagar, Perrett, Völlm, Cowen and Goodwin4,Reference Pringle, Browning, Cowen and Harmer5 Multiple paradigms accept been used to investigate emotion processing, and several, when studied in groups of younger individuals with depression, show differences broadly supporting the cognitive neuropsychological theory. For instance, using a dot probe chore, several studies have shown a bias toward distressing faces compared with neutral faces in patients experiencing a major depressive episode. Reference Bourke, Douglas and Porter6 In addition, there is a bias in individuals with low toward perceiving positive (happy), neutral or ambiguous facial expressions as more negative or less happy, compared with those in salubrious control groups. Reference Hale, Jansen, Bouhuys and van den Hoofdakker7,Reference Leppänen, Milders, Bell, Terriere and Hietanenviii In more circuitous social processing, examined with the Reading the Heed in the Eyes Chore (RMET) and other circuitous tasks, people with low perform significantly worse than command participants. Reference Bora and Berk9

Emotion Processing in Anxiety

In younger adults with anxiety disorders, there is the tendency for a bias toward threat-related stimuli, which is hypothesised to maintain a heightened sense of threat. For example, in facial expression recognition (FER) tasks, evidence suggests that individuals with social feet are not significantly different from healthy controls in identifying facial expressions, Reference Philippot and Douilliez10,Reference Stevens, Gerlach and Rist11 but show a tendency to misidentify neutral facial expressions as angry. Reference Bell, Bourke, Colhoun, Carter, Frampton and Porter12 Attentional bias toward threat-related stimuli has been reported in Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD), when using a dot probe job. Reference Bradley, Mogg, White, Groom and De Bono13 At that place is also evidence of increased response latencies to both feet-related words and generally negative words when using emotional Stroop (eStroop) tasks across anxiety disorders, suggesting an attentional bias toward threat-related stimuli. Reference Joyal, Wensing, Levasseur-Moreau, Leblond, Sack and Fecteaufourteen In younger adults, changes in emotion processing similar to those in other feet disorders have also been seen in Mail service-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). For example, a meta-analysis of eStroop task performance in PTSD Reference Cisler, Wolitzky-Taylor, Adams, Babson, Badour and Willemsxv establish that individuals with PTSD, compared with healthy controls, showed impairments in the eStroop task when processing trauma-related and by and large threatening, but not positive, information.

Changes in Emotion Processing in Ageing

Multiple experimental paradigms examining unlike aspects of attention and memory, likewise as meta-analysis of attention and memory in younger compared with older adults, Reference Reed, Chan and Mikelssixteen take suggested a 'positivity bias' in older adults. Reference Carstensen and DeLiema17 For example, older participants have been shown to be more than likely to remember positive images compared with negative images, whereas a preference for negative images was observed in young adults. Reference Charles, Mather and Carstensen18 This positivity bias has been demonstrated in multiple other emotion processing paradigms, including those examining autobiographical retentiveness, Reference Cuddy, Sikka, Silveira, Bai and Vanstone19,Reference Kennedy, Mather and Carstensen20 working memory, Reference Mikels, Larkin, Reuter-Lorenz and Carstensen21 attending to emotional faces Reference Mather and Carstensen22 and recall of facial expressions. Reference Sava, Krolak-Salmon, Delphin-Combe, Cloarec and Chainay23 Evidence also shows that older adults are slower and less accurate in studies investigating the effects of ageing on face perception by using tasks such as confront detection, Reference Norton, McBain and Chen24 face up identification Reference Habak, Wilkinson and Wilson25,Reference Megreya and Bindemann26 and emotion recognition. Reference Calder, Keane, Manly, Sprengelmeyer, Scott and Nimmo-Smith27–Reference Hildebrandt, Wilhelm, Schmiedek, Herzmann and Sommer29

Several theories attempt to explain this bias. Socioemotional selectivity theory, suggests that every bit fourth dimension to the finish of life becomes shorter, goals change focus and reflect a preference for emotional pregnant and satisfaction. Reference Carstensen30 This change in goals then affects how we process emotions. An alternative theory is dynamic integration theory. Reference Labouvie-Vief31 Since processing of negative affect may be more cognitively demanding, Reference Pratto and John32 this theory suggests that as we historic period, diminishing cognitive capacity (reduced capacity for processing) makes it more difficult to accept and integrate negative feelings, and therefore older adults disconnect from negative feelings, resulting in a positivity bias. Reference Labouvie-Vief, Diehl, Jain and Zhang33 However, if this theory is accurate then information technology is argued that this effect would be greatest in those with poorer or impaired cognitive function, whereas in fact, the reverse appears to exist the case. Reference Petrican, Moscovitch and Schimmack34,Reference Mather and Knight35 Furthermore, depression is associated with cognitive impairment merely, equally noted, seems to increase bias for negative material – although non necessarily the integration and processing of this. Reference Porter, Robinson, Malhi and Gallagher36

A further theory, the aging encephalon model, suggests that the changes in emotional noesis seen in older adults may be associated with age-related changes in adrenergic and amygdala function, Reference Cacioppo, Berntson, Bechara, Tranel, Hawkley, Todorov, Fiske and Prentice37 which leads to an impairment in the processing of negative stimuli. Studies practise show differences in encephalon activation associated with emotion processing equally ageing occurs, indirectly suggesting a decline in processing capacity in emotion processing areas. For instance, older adults show reduced limbic and greater cortical activation (east.g. insula, frontal cortex) during processing of emotional faces. Reference Fischer, Sandblom, Gavazzeni, Fransson, Wright and Bäckman38,Reference Gunning-Dixon, Gur, Perkins, Schroeder, Turner and Turetsky39 Some of these changes have been shown to correlate with the positivity bias. Sakaki et al, Reference Sakaki, Nga and Mathertwoscore found increased negative coupling betwixt the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) and amygdala and enhanced MPFC activity when learning emotional faces. This increase in MPFC action may indicate an attempt to overcome an age related decline in capacity of MPFC processing areas. In general, a reduction in activity of prefrontal cortical processing areas, with concomitant increased limbic activation (amygdala, basal ganglia), has also been shown in studies of depression both in young and older individuals during emotion processing, Reference Siegle, Thompson, Carter, Steinhauer and Thase41 in particular in response to sad faces. Reference Surguladze, Brammer, Keedwell, Giampietro, Young and Travis42

Inquiry in Late-Life Low (LLD) is further complicated past the consequence of historic period at disease onset. Onset of low at a later age is associated with greater neuropsychological aberration, white matter hyperintensities and a higher rate of dementia at follow-up. Reference Alexopoulos, Young and Meyers43–Reference Jacoby and Levy45 The fact that late-onset depression has non been associated with frequent episodes across the lifespan may likewise be important in determining emotion processing. It may therefore be that emotion processing deficits, if they exist, are different between early- and belatedly-onset depression.

To engagement, research examining emotion processing in older adults with mood and anxiety disorders has not been systematically synthesised. This review aims to examine this literature to understand the interactions between depression and feet disorders, cerebral turn down and the positivity bias in older adults, and their furnishings on emotion processing.

Based on the factors discussed above, our questions were as follows:

-

(a) In LLD, Tardily-Life Feet (LLA) and PTSD, does the positivity bias in old age mitigate the emotion processing abnormalities that might be expected given the evidence of negativity bias in younger people with depression or anxiety disorders?

-

(b) Are changes in emotion processing circuitry in LLD, LLA and PTSD similar to those seen in younger people with depression or anxiety?

-

(c) Are behavioural and encephalon changes unlike in people with late-onset low compared with early-onset depression, and what is the relationship between these changes and historic period-related cognitive decline?

Method

Search strategy

Upward to December 2019, a systematic review of electronic databases was carried out for relevant papers, using PubMed and Web of Science. In the initial search, the search terms used were 'low', 'feet', 'PTSD', 'bipolar', 'emotion processing', 'older persons' and 'elderly', in different permutations. Reference lists of all relevant papers were then checked to ensure inclusion of all pertinent articles. Citations of relevant articles were then followed using Web of Science to allow for capture of whatever missed articles.

Inclusion criteria

Peer-reviewed manufactures involving assessment with an emotion-based processing task and comparison of a clinical sample with a good for you command sample were included in the review. Studies examining all psychiatric disorders were to be considered; nonetheless, studies were simply found for depression, anxiety and PTSD populations. Sample participants were to be aged over 60 years and samples were to be categorised as 'older adult' or similar.

Exclusion criteria

Reasons for exclusion were comorbid major medical or neurological disorder in either group in the report, and studies involving participants with mild or greater levels of cognitive damage (Mini-Mental Land Examination score <25 or equivalent). All studies were express to English language-language publications.

Total report review

This review was undertaken with recommended Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and using the PRISMA statement to guide the search, screening and extraction process. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman46 Articles were screened by one of the reviewers, who independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of studies, to take or reject for full-text review. The same reviewer so examined the full texts of the studies that had passed initial screening, to make up one's mind if they still met inclusion criteria. If inclusion of a paper was unclear, all three co-authors discussed this, to accomplish a consensus. For each study, the following data was extracted: characteristics of the sample, including sample size, boilerplate age and baseline depression/anxiety severity; study pattern; cognitive tests used during assessment and study outcomes.

Results

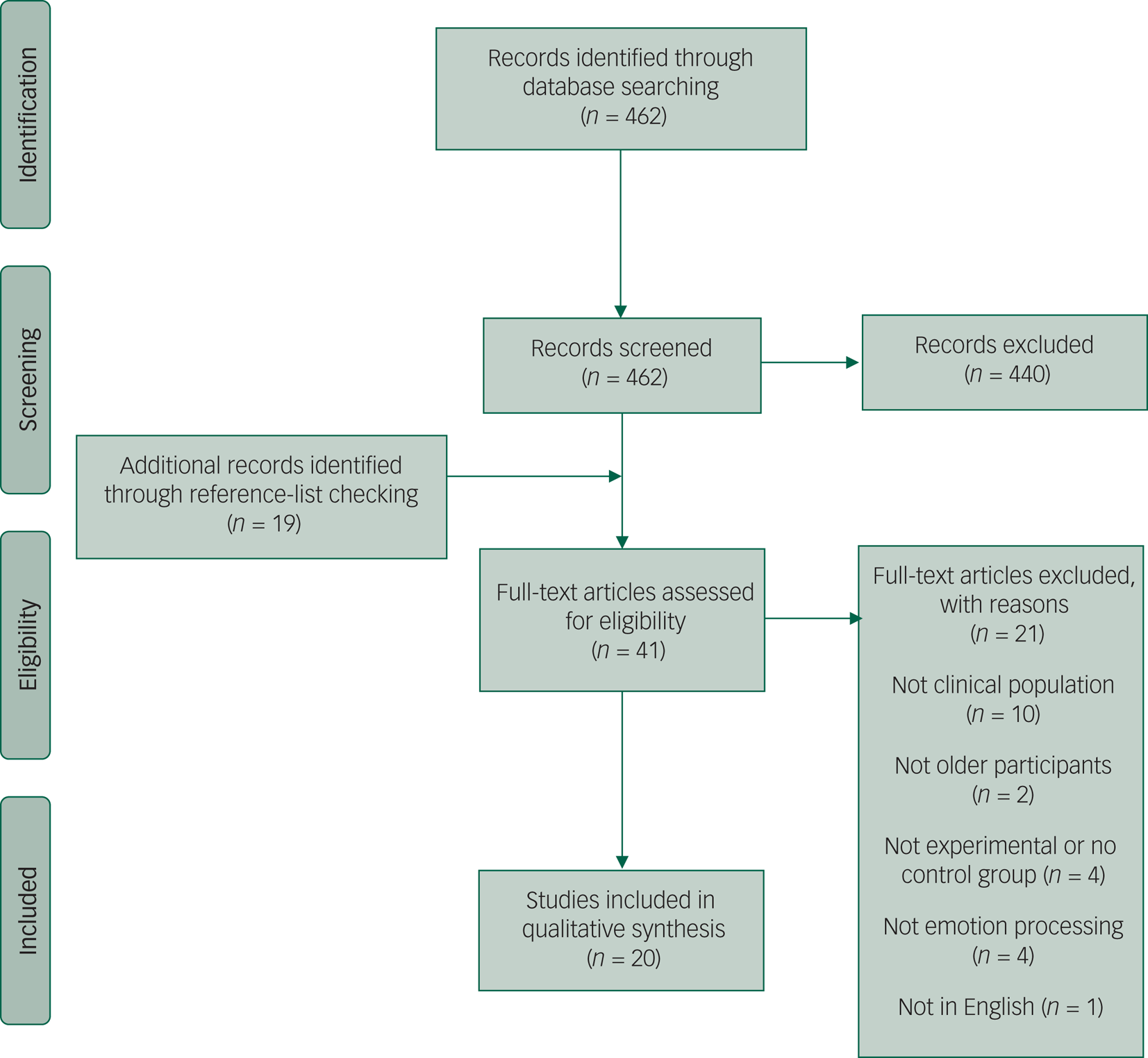

The initial search for this review found 462 articles (Fig. one). Later on a title and abstruse review, 440 of these were excluded. The total text of the remaining 22 studies were obtained and reviewed. Nineteen additional papers were found through examination of the reference sections of the full-text studies. Of these 41 studies, 21 were and so excluded for non being clinical or experimental studies, not including older participants or emotion processing, or non being in English. The remaining 20 papers are reviewed every bit follows. All of the studies included clinically diagnosed populations, unless otherwise stated. In this area of research, there is little consistency regarding terminology. LLD, depression and late- or early-onset depression are all used, with varying intended significant; equally such, we take deferred to the original authors and used the terminology that was present in the original article.

Fig. 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram of studies retrieved for the review.

Low

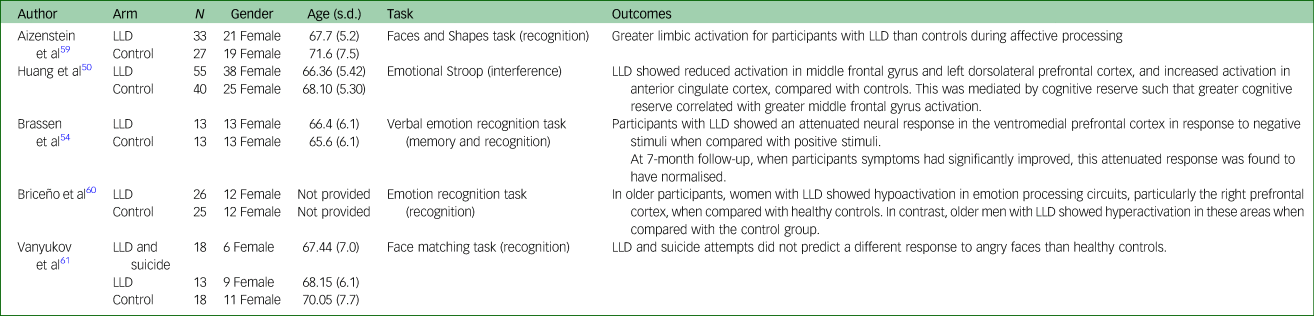

Tabular array 1 displays characteristics and main findings of studies examining behavioural data of samples with depression.

Table ane Selected demographic characteristics of included studies examining behavioural data of samples with depression

Emotion interference

The emotion processing tasks discussed in this section involve inhibition of emotional data to carry out a cognitive task. This is most commonly a modified version of the Stroop prototype (eStroop), which uses words that are of a positive, negative or neutral valence. Participants are required to name the colour of the presented word, but to ignore the word itself. A pilot study by Dudley et al Reference Dudley, O'Brien, Barnett, McGuckin and Britton47 (12 depressed, 12 controls) showed an interaction betwixt group and word valence, which was explained by a greater interference (longer time to color proper name) of depression-related words in the depressed group, with an outcome size departure compared with controls of 0.9 (Cohen's d). Broomfield et al Reference Broomfield, Davies, MacMahon, Ali and Cross48 (16 depressed, xix controls) also showed a group×valence interaction in participants with low compared with controls, with participants with depression being slower to respond to negative words compared with neutral words. The grouping×valence interaction persisted when anxiety was controlled for. Using a like eStroop prototype, Callahan and Hudon Reference Callahan and Hudon49 found those with LLD (n = 10) were generally slower than controls (n = xv), but with no departure seen across valences. No group×valence analysis was reported. Finally, in 55 people with LLD and 40 controls, using an eStroop, Reference Huang, Fan, Lee, Liu, Chen and Linl controls were more authentic and had shorter latencies. In that location was no outcome of emotion on accuracy, simply there was on latency, with both positive and negative words associated with longer latencies. There was, however, no group×emotion interaction on whatsoever of the measures. Apart from the study past Dudley et al Reference Dudley, O'Brien, Barnett, McGuckin and Britton47 , no estimates of effect size difference between depressed and control groups are given.

Mah and Pollock Reference Mah and Pollock51 used a facial emotion-based image to measure emotion inhibition in 11 participants with depression and 11 controls. In this paradigm, participants were presented with faces displaying different emotions (happy, sad, fearful and neutral) and were asked to answer questions nigh a not-affective aspect of the face (inhibition). In that location was a significant grouping×valence interaction, whereby overall latencies were similar in both groups, merely were significantly longer for all emotion-laden stimuli (not only negative emotions) compared with neutral stimuli in the command grouping and did not vary by emotion in the depressed group.

Zhou et al Reference Zhou, Dai, Rossi and Li52 studied event-related potentials (ERP), in response to emotional faces, in fourteen older adults with depressive symptoms (but specifically non meeting criteria for a DSM-IV diagnosis of depression), and compared this group with 14 controls. The study was included in the review, after give-and-take, since the patient group had meaning depressive symptoms despite no formal diagnosis (Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Calibration hateful group score of 20.21 ± v.65). Participants were presented with an emotional prime (facial expressions: happy, sad, ambiguous) and and so asked to identify the emotion of the target which followed. Older adults with depressive symptoms had smaller ERP amplitudes compared with controls, regardless of valence of the priming stimulus. Older adults with depressive symptoms showed no differences in amplitude between the different prime valences. In command participants, at that place were no differences establish betwixt happy and ambiguous primes, just there were meaning differences between happy and sad (larger ERP) primes, and betwixt cryptic and pitiful (larger ERP) primes. However, information technology was notable that the group×prime number interaction was non statistically significant (p = 0.07), making further analyses and conclusions very tentative. Behavioural information showed no differences between groups.

Emotion recognition and retention

Most commonly used is an FER task, Reference Harmer, Bhagwagar, Perrett, Völlm, Cowen and Goodwin4 in which participants are presented with various facial expressions (usually happy, sad, angry, disgusted, fearful, surprised and neutral) and asked to place the emotion portrayed. Mah and Pollock Reference Mah and Pollock51 used an FER task in which participants were presented with happy, sad, fearful or neutral faces. Although overall accuracy was similar between depressed (north = 11) and control (north = 11) groups, there was a significantly increased probability of participants with depression incorrectly identifying neutral faces.

Savaskan et al Reference Savaskan, Müller, Böhringer, Schulz and Schächinger53 used a retentiveness for faces paradigm that included both happy and angry faces. At baseline, patients with depression (n = 18) recalled fewer faces overall compared with controls (n = 22). At that place was no group×valence interaction, although the authors suggested that compared with controls, patients with depression showed lower ability to recognise previously viewed happy facial expressions subsequently a delay. Post-obit four weeks of treatment, the patient grouping showed a significant reduction in depressive symptoms and a pregnant improvement in general cerebral role. Further, their retentivity for angry faces significantly improved from baseline, whereas no effect was seen for happy faces.

Two studies examined emotion recognition and memory for emotional material, using verbal stimuli. Brassen et al Reference Brassen, Kalisch, Weber-Fahr, Braus and Buechel54 used an emotion recognition task with positive, neutral and negative words to examine neural responses in 13 antidepressant-naïve female person patients with LLD versus xiii controls. Participants were shown a positive, negative or neutral adjective, which was then replaced by a response screen where they indicated the valence of the word. No meaning differences in response correctness, response time or misattributions of emotion were found at either time point between the 2 groups.

Callahan et al Reference Callahan, Simard, Mouiha, Rousseau, Laforce and Hudon55 examined recall of neutral, positive and negative words from a list including 12 of each. At firsthand recall, control participants (n = 28) displayed better retrieve of positive and negative words compared with neutral words, whereas participants with low (n = nineteen) recalled more negative than neutral words. Nevertheless, performance of the 2 groups was non directly compared. At delayed retrieve, both groups generally showed better recollect of emotional compared with neutral words. During recognition, all participants were more likely to report false recognition for emotional than neutral words. Once once again, there was no group comparison.

Social cognition

The RMET Reference Businesswoman-Cohen, Wheelwright, Hill, Raste and Plumb56 requires individuals to place complex or social emotions from images portraying only the eyes of the face. Szanto et al Reference Szanto, Dombrovski, Sahakian, Mulsant, Houck and Reynolds57 examined the RMET in older adults with depression who had (due north = 24) or had not (northward = 38) attempted suicide. A command grouping was too examined (n = 28). Individuals who had attempted suicide performed significantly worse than healthy controls. The operation of participants with depression who had not attempted suicide fell between controls and those who had attempted suicide, merely was not significantly different from either. Further analysis showed that when global cognitive office was accounted for (Mattis Dementia Rating Scale Reference Mattis58), the pregnant difference found for individuals who had attempted suicide was non maintained, suggesting that the grouping'south reduced ability to recognise social emotions may have been attributable to global cognitive impairment, rather than a specific impairment in social cognition.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies

Tabular array 2 displays characteristics and primary findings of studies examining neuroimaging information of samples with depression.

Table 2 Selected demographic characteristics of included studies examining neuroimaging data of samples with depression

Aizenstein et al Reference Aizenstein, Andreescu, Edelman, Cochran, Price and Butters59 used a facial expression affective-reactivity job. Participants with depression (northward = 33) showed greater subgenual cingulate activity during melancholia processing compared with controls (n = 27) with a meaning correlation between white matter hyperintensity and activeness. Huang et al Reference Huang, Fan, Lee, Liu, Chen and Linl (55 participants with LLD, twoscore controls) showed reduced activation in middle frontal gyrus and left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and increased activation in anterior cingulate cortex, in the LLD group compared with controls in a study examining activation during an eStroop task. This was mediated by cognitive reserve such that greater cognitive reserve correlated with greater centre frontal gyrus activation in the LLD group. Brassen et al Reference Brassen, Kalisch, Weber-Fahr, Braus and Buechel54 reported that in comparing with controls (north = 13), female patients with LLD (n = 13) showed attenuated neural response in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in response to negative compared with positive words. When correlated with depression severity in the depressed grouping (Geriatric Low Scale), reduced activation in the medial orbito-frontal cortex was correlated with higher depression scores. Increased activation in the superior medial frontal cortex, for positive compared with negative words, was also correlated with higher low scores. At the vii-month follow-upward, when patients' symptoms had significantly improved, this attenuated response was found to have normalised.

Briceño et al Reference Briceño, Rapport, Kassel, Bieliauskas, Zubieta and Weisenbachlx examined the effects of age and gender on neural circuits in an FER paradigm that involved four emotions (happiness, sadness, fear and anger). The study included participants in younger and older historic period groups, too as participants with and without depression (older participants with depression, n = 26; older controls, due north = 25). When depressed and not-depressed groups were not separated by age and gender, no overall effects were detected between groups. However, when separated by historic period and gender, older women with depression showed hypoactivation in emotion processing circuits, particularly the correct prefrontal cortex, when compared with older controls. In dissimilarity, older males with depression showed hyperactivation in these areas when compared with the control group.

Vanyukov et al Reference Vanyukov, Szanto, Siegle, Hallquist, Reynolds and Aizenstein61 used the faces and shapes task, Reference Hariri, Mattay, Tessitore and Kolachana62 in which participants are required to match a target confront to one of 2 presented faces. Authors used faces showing anger and fearfulness during the face trials. In neutral trials, shapes were used as non-affective controls. The report examined patients with depression (northward = thirteen), patients with low who had attempted suicide (n = 18) and controls (due north = xviii). There was no departure in response to aroused faces in either depressed group compared with controls. Responses to fear-related stimuli were not discussed.

Anxiety disorders

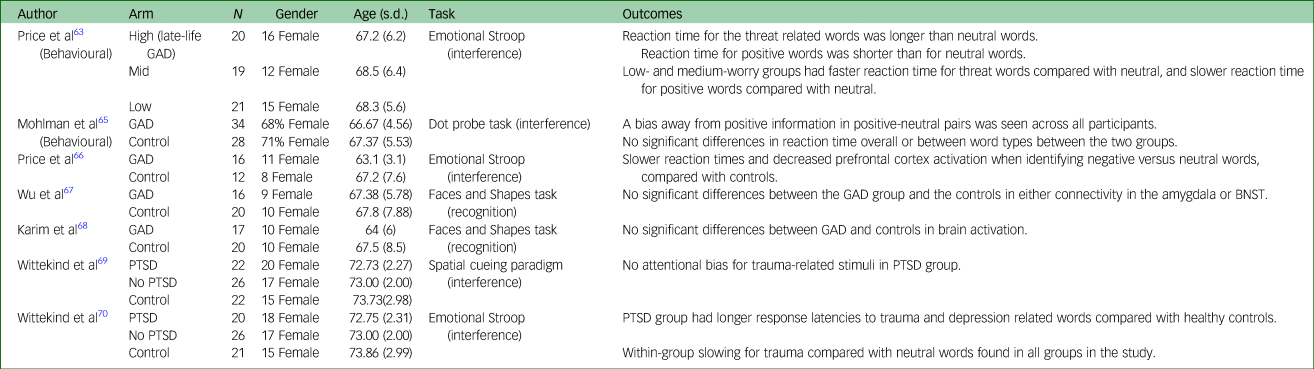

Table 3 presents characteristics and fundamental findings from reviewed studies examining samples with anxiety disorders.

Tabular array 3 Selected demographic characteristics of included studies examining anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder

Price et al Reference Cost, Siegle and Mohlman63 divided 60 customs recruited adults into loftier-, medium- and depression-trait anxiety, based on responses to the Penn Country Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ). A full of 90% of participants in the loftier-worry group (north = twenty) scored ≥50 on the PSWQ, which has been noted as a cutting-off for late-life GAD. Reference Webb, Diefenbach, Wagener, Novy, Kunik and Rhoades64 The remaining participants (north = twoscore) formed comparing groups. An eStroop task containing positive, threat-related, and neutral words was used. In the high-worry group, response time for threat-related words was longer than neutral words (Cohen's d = 0.76). The high-worry group also showed faster reaction times for positive words than neutral. The low- and medium-worry groups showed the opposite pattern: faster response time for threat-related words compared with neutral, and slower response time for positive words compared with neutral. Betwixt-group comparisons of estimated marginal means showed a difference between the high-worry and low-worry group, with bias toward threat-related words being greater (Cohen'southward d = 0.67).

Mohlman et al Reference Mohlman, Toll and Vietri65 used a dot probe chore which included depression, threat, positive and neutrally valenced words to examine attentional biases. There was no significant between-grouping differences in reaction fourth dimension overall or between word types in GAD (due north = 34) versus controls (north = 28). Using differences between probe-target congruent word pairs and incongruent pairs, bias scores were calculated. No significant differences in bias scores between GAD and command groups were found. A bias abroad from positive data in positive–neutral pairs was seen across all participants in the study. No meaning change in performance post-obit treatment (cognitive–behavioural therapy versus waitlist) was found.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies

Price et al Reference Price, Eldreth and Mohlman66 examined functional magnetic resonance imaging responses to functioning on an eStroop task in older adults with late-life GAD. Participants with GAD (n = 16) had slower reaction times when responding to negative versus neutral words, compared with controls (due north = 12) (Cohen'due south d = 0.85), and also showed less activation in the prefrontal cortex in response to negative compared with neutral words. An increase in activation was seen in the GAD grouping in the left amygdala, compared with the control grouping.

Ii studies Reference Wu, Mennin, Ly, Karim, Banihashemi and Tudorascu67,Reference Karim, Tudorascu, Aizenstein, Walker, Good and Andreescu68 examined functional connectivity associated with emotional reactivity in late-life GAD compared with good for you controls. Neither study found any significant differences betwixt the GAD group and the controls, using a faces and shapes task. Both studies examined the data using the gene of worry, as measured by the PSWQ. Wu et al Reference Wu, Mennin, Ly, Karim, Banihashemi and Tudorascu67 found that in that location was a significant interaction betwixt group and 'worry' on connectivity between the left amygdala and left orbitofrontal cortex, MPFC and both anterior cingulate cortices, and on connectivity between the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and the left orbitofrontal cortex. When worry was examined across groups, there was a U-shaped curve, whereby connectivity between limbic and cortical areas was optimal at medium levels of 'worry'. The event sizes of these curves varied from r 2 = 0.21 to r two = 0.25. Karim et al Reference Karim, Tudorascu, Aizenstein, Walker, Skillful and Andreescu68 found that across the groups, increased global anxiety, measured by the Hamilton Feet and Depression Scale, was associated with greater activation in the parahippocampal area and precuneus. In contrast, worry (PSWQ) was associated with decreased precuneus and prefrontal activation. Circuitous arbitration analyses broadly suggested that the arbitration between increased white matter hyperintensity burden and anxiety symptoms are mediated past increased activation of limbic and paralimbic structures, and decreased activation of regulatory regions, such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

PTSD

I study, published as two papers, examined emotion processing in older populations with PTSD. Wittekind et al Reference Wittekind, Muhtz, Jelinek and Moritz69 used a spatial cueing chore involving priming with an emotional facial stimulus (anxiety, depression, trauma and neutral), followed by a spatial (left or right) decision, in response to a not-affective target (26 participants with PTSD, 22 controls). Authors found no attentional biases within the PTSD grouping for trauma-related stimuli. However, postal service hoc redistribution of participants into those who did or did not meet the criteria for depression showed that participants in the depressed sample had longer reaction times to depressive stimuli (Cohen's d = 1.5).

The same participants likewise completed an eStroop job Reference Wittekind, Muhtz, Moritz and Jelinek70 containing words related to depression, trauma, anxiety or neutral words. Participants with PTSD showed longer response latencies to trauma- and depression-related words compared with good for you controls, but no differences in latency for neutral and anxious words. Slowing for trauma compared with neutral words was found across all groups in this report.

Discussion

The chief findings of the review were every bit follows. Get-go, at a behavioural level, bear witness regarding differences in emotion processing between individuals with LLD and controls is inconsistent. This is the instance for interference of emotional material in cerebral processes (eStroop), memory for emotional compared with other material, and the explicit process of recognition of emotional facial expressions. 2nd, at that place are few studies in LLA. Studies suggest interference with processing by threat related words in anxiety and by trauma-related words in PTSD, but in that location are no replication studies. Finally, studies testify differences in activation in emotional processing circuitry in LLD, with the general pattern of increased limbic but reduced prefrontal activity, as in younger individuals with depression.

The review more than specifically examined iii primary questions as below.

How does the positivity bias seen in older persons interact with biases toward negative or threat-related emotional material in depression or anxiety?

There are no consistent findings regarding any of the aspects of emotion processing studied. This was the case both for implicit processes (such as the eStroop) and for explicit processes (such every bit emotion recognition). Non all of these phenomena have been consistently replicated in younger people with depression either. For instance, results on the eStroop have not been found to be consistent. Reference Epp, Dobson, Dozois and Frewen71 The phenomenon seen most consistently in younger low is the misinterpretation of, or attentional bias toward, neutral faces. Reference Bourke, Douglas and Porterhalf dozen,Reference Harmer, Goodwin and Cowen72 In LLD, this was only examined in three studies and was not seen consistently.

The lack of consequent evidence of bias toward negative emotional stimuli in LLD may reflect a situation in which, on average, negative bias is less in LLD than in younger depression. It could be hypothesised that this relates to the positivity bias associated with ageing, which counteracts the biases seen in depression. Nonetheless, the inconsistencies in the information are more likely to be related to the small numbers of studies and limited ability of nigh studies. Further issues with the data are that there are no studies directly comparison emotion processing between younger patients with depression and LLD. Similarly no comparisons across the lifespan have been conducted in anxiety disorders. Therefore, the interaction of age with depression or anxiety cannot exist fully evaluated. Finally, studies generally did not examine possible complicating factors, such as concomitant cognitive impairment, historic period at affliction onset and the furnishings of medication.

Are changes in emotion processing circuitry similar to those seen in younger people with low or anxiety?

In younger people with depression, studies have by and large shown a reduction in activity of dorsal-cognitive structures combined with increased activity of ventral-affective structures during emotion processing. Reference Roiser, Elliott and Sahakian73 The studies in LLD are broadly in line with this blueprint with the largest studies showing increased activation of limbic structures or decreased activation of prefrontal structures in LLD compared with controls, in line with a general pattern of reduced elevation-downwards processing. Reference Huang, Fan, Lee, Liu, Chen and Lin50,Reference Brassen, Kalisch, Weber-Fahr, Braus and Buechel54,Reference Aizenstein, Andreescu, Edelman, Cochran, Price and Butters59

Of interest, there was as well evidence of an interaction between depression and both white matter lesions Reference Aizenstein, Andreescu, Edelman, Cochran, Toll and Butters59 and cognitive reserve Reference Huang, Fan, Lee, Liu, Chen and Lin50 in determining patterns of activation during emotional processing. White matter changes were associated with an exaggeration of the increase in subgenual cingulate activation seen during emotion processing in LLD. Reference Aizenstein, Andreescu, Edelman, Cochran, Cost and Butters59 In the study of Huang et al Reference Huang, Fan, Lee, Liu, Chen and Linfifty, severity of depression was associated with reduced medial frontal activation during emotion processing, but this was attenuated by having greater cognitive reserve (measured using years of education and verbal fluency). Both findings propose a situation in which if processing capacity is reduced for a diversity of possible reasons, this may impair efficient emotion processing, resulting in processing being driven to a greater extent by limbic structures.

Are behavioural and brain changes different in people with late-onset compared with early-onset depression, and what is the relationship betwixt these changes and age-related cerebral refuse?

Of notation, our review excluded studies in which participants had a Mini-Mental State Test score < 25. The rationale was that although we were interested in the interaction between mood and anxiety, cognitive ability and the relationship of these to emotion processing and positivity bias, we wanted to restrict the review to examining LLD and LLA and not to extend this into dementia. Four studies did examine the relationship between emotional processing and other aspects of cognitive performance. Callahan et al Reference Callahan, Simard, Mouiha, Rousseau, Laforce and Hudon55 examined the influence of depression on emotion processing in mild cerebral damage (MCI), based on the proposition that MCI plus depression is particularly likely to progress to dementia, and therefore constitutes a prognostically important subtype of MCI. Reference Rosenberg, Mielke, Appleby, Oh, Geda and Lyketsos74,Reference Apostolova and Cummings75 Consistent with the hypothesis that negative information requires greater capacity to process, Callahan et al Reference Callahan, Simard, Mouiha, Rousseau, Laforce and Hudon55 showed that for patients with MCI, immediate recall was better for positive words than negative words; all the same, this was not the case for MCI with depression, healthy controls or LLD. A caveat to this determination is the lack of an assay of group×valence interaction. Furthermore, a similar effect was not seen in a divide examination of effects on an eStroop examination. Reference Callahan and Hudon49 Although Huang et al Reference Huang, Fan, Lee, Liu, Chen and Lin50 did not find the hypothesised eStroop outcome in LLD, there was more preserved heart frontal gyrus activity during eStroop performance in people with greater cognitive reserve. This suggests that cerebral reserve (measured using a combination of years of education and an executive chore) mediates a more height-downwardly emotional regulation, i.e. preserved processing capacity in those with greater cerebral reserve. Szanto et al Reference Szanto, Dombrovski, Sahakian, Mulsant, Houck and Reynolds57 examined social cognition in LLD. Those who attempted suicide had lower scores than controls but, interestingly, this did non survive covarying for general cognitive function, suggesting that the two functions are related, at least in depression.

Specific issues in late-life feet disorders

Five studies examining emotion processing in LLA disorders were identified. Those using an eStroop chore both showed increased latency for negatively valenced words. Reference Price, Siegle and Mohlman63,Reference Price, Eldreth and Mohlman66 In one of the studies which examined brain activation, Reference Price, Eldreth and Mohlman66 the hypothesised deviation from controls was seen, with an increment in activation of role of the amygdala, accompanied by a decrease in activation of the dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex in older patients with GAD. Ii farther studies showed no deviation between patients with GAD and controls, Reference Wu, Mennin, Ly, Karim, Banihashemi and Tudorascu67,Reference Karim, Tudorascu, Aizenstein, Walker, Good and Andreescu68 in brain activation and connectivity. However, in i there was a complex relationship betwixt worry and connectivity, suggesting that connectivity between limbic and cortical areas was maximal at an intermediate level of worry. Reference Toll, Eldreth and Mohlman66 In the other study, Reference Wu, Mennin, Ly, Karim, Banihashemi and Tudorascu67 anxiety was associated with greater activation in parahippocampal areas and precuneus. In general this is in keeping with attenuation of activity in, and connectivity with, processing areas seen in younger patients. Reference Goossen, van der Starre and van der Heiden76

Data regarding interference by trauma-related words in eStroop tasks has been consistently demonstrated in younger adults with PTSD. Reference Cisler, Wolitzky-Taylor, Adams, Babson, Badour and Willems15 Both in LLA and PTSD, studies examining simple attending bias toward negative stimuli have not shown a deviation from controls. Reference Mohlman, Price and Vietri65,Reference Wittekind, Muhtz, Jelinek and Moritz69 This may propose that the basic focus of attention is not altered, but that negative emotional stimuli exercise interfere with processing.

Limitations and recommendations for future enquiry

This review has limitations both directly related to the methodology and to the content of the studies reviewed. Related directly to the review, information technology considered English-language papers only. Although this is standard do for an English language-language review, it may hateful that some relevant studies accept been missed. 2d, meta-analysis has not been possible given the heterogeneity of paradigms investigated in the studies examined, and in the variety of ways the data has been analysed and presented.

Limitations of the data, which can be translated into recommendations for the field are, as follows. Start, although studies are in 'older adults', the bulk take mean ages from 65 to 75 years, with the lower age cutting-off beingness 60 years in about studies. This may hateful that furnishings of age that might have been seen, for example, in lxx–fourscore yr olds, are washed out by in that location beingness relatively less issue in the lower age range. This could, of class, be overcome past studies being adequately powered to examine the furnishings of age in a linear fashion – possibly fifty-fifty over a larger age range then that the effects of age and its interaction with depression or anxiety could be examined. This would better reflect the fact that take chances factors and neurobiology likely modify in a linear fashion across the lifespan. Reference Schaakxs, Comijs, van der Mast, Schoevers, Beekman and Penninx77 Second, about studies did not analyse the effects of having early-onset compared with late-onset low. Once again the issue is mainly i of ability and as such this should be examined with sufficiently large studies. Third, a diversity of paradigms take been used to report emotion processing even inside similar processes. This makes it generally difficult to puddle or synthesise results from dissimilar studies. Consensus on the most useful and clinically relevant paradigms would aid progress in the field. Quaternary, studies accept rarely attempted to determine the extent to which pass up in not-emotional cognitive processes, such as executive function, may exist affecting emotional processing directly. Future studies should consider undertaking testing of non-emotional memory and executive part and examining the relationship between this and emotion processing. 5th, critically, studies accept tended to exist very small. Future studies should be adequately powered to show differences at least as pocket-size as 0.5 s.d. between groups. They should also, ideally, exist big plenty to take into account the possible furnishings of varying medication, late compared with early onset and age every bit a longitudinal factor on emotion processing. Finally, in reporting results, about studies use analysis of variance but practise not report estimated marginal means and south.d., making it impossible to calculate the magnitude of differences between groups. These should be reported or event sizes calculated.

In conclusion, the ability to correctly procedure and interpret emotions is an of import part of social interactions, something that becomes peculiarly of import as we age. The cognitive neuropsychological hypothesis of low also suggests that these interactions are an of import part of the aetiology of depression and may provide a target for treatment. Indeed, packages of emotion recognition training are beingness developed to address this consequence (due east.g. the study by Penton-Voak et al Reference Penton-Voak, Adams, Push button, Fluharty, Dalili and Browning78).

The review has highlighted the fact that there are relatively few big studies of emotion processing in older adults with depression and anxiety disorders. Nosotros have provided recommendations for future inquiry.

Given the lack of studies that examine emotion processing in depression or anxiety across the life wheel, information technology is non possible to decide the interaction of abnormalities in these weather with the ageing positivity bias. In general, there have been findings of a bias toward negative stimuli, and concomitant alteration of brain activity to a pattern of greater limbic and reduced prefrontal cortex activation in younger people with depression and feet. Similar patterns have been shown in studies in older persons, although non consistently in some aspects of emotion processing.

Author contributions

Five.G. conducted the systematic review of papers and prepared the beginning draft of the manuscript. R.J.P. and M.One thousand.D. supervised the systematic review and reviewed and updated subsequent drafts.

Funding

We are grateful to the University of Otago for financial support, by providing V.G. with the Gilbert M. Tothill Scholarship in Psychological Medicine.

Proclamation of interest

V.G. has nothing to disclose. M.G.D. uses software for cognitive remediation intervention research that is provided gratis of charge by Scientific Encephalon Training PRO. R.J.P. uses computer software at no price, provided by SBT-Pro, for research. He has received support for travel to educational meetings from Servier and Lundbeck.

References

Dark-green, MF , Hellemann, G , Horan, WP , Lee, J , Wynn, JK . From perception to functional upshot in schizophrenia: modeling the role of power and motivation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012; 69(12): 1216–24.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Warren, MB , Pringle, A , Harmer, CJ . A neurocognitive model for agreement treatment action in depression. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 2015; 370(1677): 20140213.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Disner, SG , Beevers, CG , Haigh, EA , Brook, AT . Neural mechanisms of the cognitive model of depression. Nat Rev Neurosci 2011; 12(eight): 467–77.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Harmer, CJ , Bhagwagar, Z , Perrett, DI , Völlm, BA , Cowen, PJ , Goodwin, GM . Acute SSRI administration affects the processing of social cues in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28(1): 148–52.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Pringle, A , Browning, Thou , Cowen, PJ , Harmer, CJ . A cognitive neuropsychological model of antidepressant drug activity. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2011; 35(vii): 1586–92.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Bourke, C , Douglas, K , Porter, R . Processing of facial emotion expression in major depression: a review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2010; 44(8): 681–96.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Hale, WW 3 , Jansen, JHC , Bouhuys, AL , van den Hoofdakker, RH . The judgment of facial expressions by depressed patients, their partners and controls. J Affect Disord 1998; 47(1): 63–70.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Leppänen, JM , Milders, Yard , Bell, JS , Terriere, East , Hietanen, JK . Depression biases the recognition of emotionally neutral faces. Psychiatry Res 2004; 128(two): 123–33.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Bora, E , Berk, G . Theory of listen in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2016; 191: 49–55.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Philippot, P , Douilliez, C . Social phobics do not misinterpret facial expression of emotion. Behav Res Ther 2005; 43(5): 639–52.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Stevens, S , Gerlach, AL , Rist, F . Effects of booze on ratings of emotional facial expressions in social phobics. J Feet Disord 2008; 22(6): 940–viii.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Bell, C , Bourke, C , Colhoun, H , Carter, F , Frampton, C , Porter, R . The misclassification of facial expressions in generalised social phobia. J Anxiety Disord 2011; 25(2): 278–83.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Bradley, BP , Mogg, Thou , White, J , Groom, C , De Bono, J . Attentional bias for emotional faces in generalized anxiety disorder. Br J Clin Psychol 1999; 38(iii): 267–78.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Joyal, Grand , Wensing, T , Levasseur-Moreau, J , Leblond, J , Sack, AT , Fecteau, S . Characterizing emotional Stroop interference in posttraumatic stress disorder, major depression and anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-assay. PLoS 1 2019; 14(4): e0214998.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Cisler, JM , Wolitzky-Taylor, KB , Adams, TG Jr , Babson, KA , Badour, CL , Willems, JL . The emotional Stroop chore and posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2011; 31(5): 817–28.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Reed, AE , Chan, L , Mikels, JA . Meta-analysis of the age-related positivity effect: historic period differences in preferences for positive over negative information. Psychol Crumbling 2014; 29(1): 1–15.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Carstensen, LL , DeLiema, M . The positivity effect: a negativity bias in youth fades with historic period. Curr Opin Behav Sci 2018; xix: 7–12.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Charles, ST , Mather, Yard , Carstensen, LL . Aging and emotional retention: the forgettable nature of negative images for older adults. J Exp Psychol Gen 2003; 132(2): 310–24.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Cuddy, LL , Sikka, R , Silveira, K , Bai, S , Vanstone, A . Music-evoked autobiographical memories (MEAMs) in Alzheimer disease: evidence for a positivity effect. Cog Psychol 2017; 4(1): 1277578.Google Scholar

Kennedy, Q , Mather, 1000 , Carstensen, LL . The role of motivation in the age-related positivity effect in autobiographical retentiveness. Psychol Sci 2004; fifteen(three): 208–14.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Mikels, JA , Larkin, GR , Reuter-Lorenz, PA , Carstensen, LL . Divergent trajectories in the aging mind: changes in working memory for affective versus visual information with age. Psychol Aging 2005; 20(4): 542–53.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Sava, A-A , Krolak-Salmon, P , Delphin-Combe, F , Cloarec, Yard , Chainay, H . Memory for faces with emotional expressions in Alzheimer'southward illness and healthy older participants: positivity effect is not only due to familiarity. Aging. Neuropsychol Cogn 2017; 24(1): 1–28.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Norton, D , McBain, R , Chen, Y . Reduced ability to find facial configuration in middle-aged and elderly individuals: associations with spatiotemporal visual processing. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2009; 64(iii): 328–34.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Habak, C , Wilkinson, F , Wilson, Hour . Aging disrupts the neural transformations that link facial identity across views. Vision Res. 2008; 48(1): nine–15.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Megreya, AM , Bindemann, M . Developmental improvement and age-related turn down in unfamiliar face up matching. Perception 2015; 44(1): v–22.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Calder, AJ , Keane, J , Manly, T , Sprengelmeyer, R , Scott, S , Nimmo-Smith, I , et al. Facial expression recognition across the adult life span. Neuropsychologia 2003; 41(2): 195–202.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Hildebrandt, A , Wilhelm, O , Herzmann, G , Sommer, West . Face up and object cognition beyond adult age. Psychol Aging 2013; 28(1): 243–48.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Hildebrandt, A , Wilhelm, O , Schmiedek, F , Herzmann, Thou , Sommer, West . On the specificity of face cognition compared with general cognitive performance across developed age. Psychol Aging 2011; 26(3): 701–15.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Labouvie-Vief, Yard . Dynamic integration: bear on, cognition, and the self in adulthood. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2003; 12(6): 201–half-dozen.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Pratto, F , John, OP . Automatic vigilance: the attention-grabbing ability of negative social information. J Pers Soc Psychol 1991; 61(three): 380–92.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Labouvie-Vief, Grand , Diehl, 1000 , Jain, Eastward , Zhang, F . Half dozen-year change in affect optimization and affect complexity beyond the developed life bridge: a further examination. Psychol Aging 2007; 22(4): 738–51.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Petrican, R , Moscovitch, M , Schimmack, U . Cognitive resources, valence, and memory retrieval of emotional events in older adults. Psychol Aging 2008; 23(3): 585–94.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Mather, M , Knight, M . Goal-directed memory: the part of cognitive command in older adults' emotional memory. Psychol Aging 2005; twenty(four): 554–seventy.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Porter, RJ , Robinson, LJ , Malhi, GS , Gallagher, P . The neurocognitive profile of mood disorders–a review of the evidence and methodological issues. Bipolar Disord 2015; 17: 21–xl.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Cacioppo, JT , Berntson, GG , Bechara, A , Tranel, D , Hawkley, LC . Could an aging brain contribute to subjective well-beingness? The value added by a social neuroscience perspective. In Oxford Series in Social Cognition and Social Neuroscience. Social Neuroscience: Toward Understanding the Underpinnings of the Social Mind (eds Todorov, A , Fiske, ST , Prentice, DA ): 249–62. Oxford Academy Press, 2011.Google Scholar

Fischer, H , Sandblom, J , Gavazzeni, J , Fransson, P , Wright, CI , Bäckman, 50 . Age-differential patterns of brain activation during perception of angry faces. Neurosci Lett 2005; 386(2): 99–104.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Gunning-Dixon, FM , Gur, RC , Perkins, Air conditioning , Schroeder, L , Turner, T , Turetsky, BI , et al. Age-related differences in brain activation during emotional face up processing. Neurobiolf Aging 2003; 24(two): 285–95.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Sakaki, M , Nga, L , Mather, M . Amygdala functional connectivity with medial prefrontal cortex at rest predicts the positivity upshot in older adults' retention. J Cogn Neurosci 2013; 25(8): 1206–24.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Siegle, GJ , Thompson, W , Carter, CS , Steinhauer, SR , Thase, ME . Increased amygdala and decreased dorsolateral prefrontal BOLD responses in unipolar depression: related and independent features. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 61(2): 198–209.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Surguladze, S , Brammer, MJ , Keedwell, P , Giampietro, V , Young, AW , Travis, MJ , et al. A differential pattern of neural response toward sad versus happy facial expressions in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 57(iii): 201–9.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Alexopoulos, GS , Young, RC , Meyers, BS . Geriatric low: age of onset and dementia. Biol Psychiatry 1993; 34(3): 141–five.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Alexopoulos, GS , Young, RC , Shindledecker, RD . Brain computed tomography findings in geriatric low and main degenerative dementia. Biol Psychiatry 1992; 31(6): 591–ix.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Jacoby, RJ , Levy, R . Computed tomography in the elderly three. Melancholia disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1980; 136(3): 270–5.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Moher, D , Liberati, A , Tetzlaff, J , Altman, DG . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009; 339: b2535.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Dudley, R , O'Brien, J , Barnett, N , McGuckin, L , Britton, P . Distinguishing low from dementia in later life: a pilot study employing the emotional Stroop job. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 17(1): 48–53.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Broomfield, NM , Davies, R , MacMahon, K , Ali, F , Cantankerous, SMB . Farther evidence of attention bias for negative information in late life depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007; 22(iii): 175–80.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Callahan, BL , Hudon, C . Emotional Stroop operation: further prove for distinct cognitive patterns in depressed and non-depressed aMCI. Alzheimer'due south & Dement 2014; 10(suppl four): P434.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Huang, C-M , Fan, Y-T , Lee, S-H , Liu, H-L , Chen, Y-L , Lin, C , et al. Cognitive reserve-mediated neural modulation of emotional control and regulation in people with tardily-life depression. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2019; xiv(8): 849–sixty.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Mah, 50 , Pollock, BG . Emotional processing deficits in late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010; 18(7): 652–half-dozen.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Zhou, H , Dai, B , Rossi, S , Li, J . Electrophysiological evidence for elimination of the positive bias in elderly adults with depressive symptoms. Front Psychiatry 2018; 9: 62.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Savaskan, E , Müller, SE , Böhringer, A , Schulz, A , Schächinger, H . Antidepressive therapy with escitalopram improves mood, cognitive symptoms, and identity memory for angry faces in elderly depressed patients. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2008; 11(3): 381–8.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Brassen, S , Kalisch, R , Weber-Fahr, W , Braus, DF , Buechel, C . Ventromedial prefrontal cortex processing during emotional evaluation in late-life depression: a longitudinal functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 64(4): 349–55.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Callahan, BL , Simard, M , Mouiha, A , Rousseau, F , Laforce, R , Hudon, C . Impact of depressive symptoms on retentiveness for emotional words in mild cognitive damage and late-life depression. J Alzheimers Dis 2016; 52(ii): 451–62.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Baron-Cohen, S , Wheelwright, S , Hill, J , Raste, Y , Plumb, I . The 'Reading the Mind in the Eyes' examination revised version: a written report with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2001; 42(ii): 241–51.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Szanto, K , Dombrovski, AY , Sahakian, BJ , Mulsant, BH , Houck, PR , Reynolds, CF 3rd, et al. Social emotion recognition, social functioning, and attempted suicide in belatedly-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012; 20(3): 257–65.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Mattis, S . Dementia Rating Scale (DRS): Professional Transmission. Psychological Assessment Resources, 1988.Google Scholar

Aizenstein, H , Andreescu, C , Edelman, K , Cochran, J , Price, J , Butters, M , et al. fMRI correlates of white matter hyperintensities in late-life low. Am J Psychiatry 2011; 168(x): 1075–82.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Briceño, EM , Rapport, LJ , Kassel, MT , Bieliauskas, LA , Zubieta, J-Chiliad , Weisenbach, SL , et al. Age and gender attune the neural circuitry supporting facial emotion processing in adults with major depressive disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015; 23(3): 304–xiii.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Vanyukov, PM , Szanto, Grand , Siegle, GJ , Hallquist, MN , Reynolds, CF III , Aizenstein, HJ , et al. Impulsive traits and unplanned suicide attempts predict exaggerated prefrontal response to angry faces in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015; 23(8): 829–39.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Hariri, AR , Mattay, VS , Tessitore, A , Kolachana, B , et al. Serotonin transporter genetic variation and the response of the homo amygdala. Science 2002; 297(5580): 400–iii.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Price, RB , Siegle, G , Mohlman, J . Emotional Stroop performance in older adults: effects of habitual worry. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012; 20(ix): 798–805.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Webb, SA , Diefenbach, K , Wagener, P , Novy, DM , Kunik, M , Rhoades, HM , et al. Comparison of self-written report measures for identifying late-life generalized feet in primary care. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2008; 21(four): 223–31.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Mohlman, J , Price, RB , Vietri, J . Attentional bias in older adults: effects of generalized anxiety disorder and cognitive behavior therapy. J Feet Disord 2013; 27(6): 585–591.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Price, RB , Eldreth, DA , Mohlman, J . Deficient prefrontal attentional control in late-life generalized anxiety disorder: an fMRI investigation. Transl Psychiatry 2011; 1: e46.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Wu, M , Mennin, DS , Ly, M , Karim, HT , Banihashemi, L , Tudorascu, DL , et al. When worry may be healthy: worry severity and limbic-prefrontal functional connectivity in belatedly-life generalized anxiety disorder. J Affect Disord 2019; 257: 650–7.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Karim, H , Tudorascu, DL , Aizenstein, H , Walker, S , Proficient, R , Andreescu, C . Emotion reactivity and cerebrovascular burden in late-life GAD: a neuroimaging study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016; 24(eleven): 1040–fifty.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Wittekind, CE , Muhtz, C , Jelinek, L , Moritz, Southward . Depression, not PTSD, is associated with attentional biases for emotional visual cues in early traumatized individuals with PTSD. Front Psychol 2015; 5: 1474.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Wittekind, CE , Muhtz, C , Moritz, Southward , Jelinek, L . Operation in a blocked versus randomized emotional Stroop task in an aged, early traumatized group with and without posttraumatic stress symptoms. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2017; 54: 35–43.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Epp, AM , Dobson, KS , Dozois, DJ , Frewen, PA . A systematic meta-analysis of the Stroop task in depression. Clin Psychol Rev 2012; 32(iv): 316–28.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Harmer, CJ , Goodwin, GM , Cowen, PJ . Why do antidepressants take so long to work? A cerebral neuropsychological model of antidepressant drug action. Br J Psychiatry 2018; 195(two): 102–eight.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Roiser, JP , Elliott, R , Sahakian, BJ . Cognitive mechanisms of handling in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012; 37(1): 117–36.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Rosenberg, Atomic number 82 , Mielke, MM , Appleby, BS , Oh, ES , Geda, YE , Lyketsos, CG . The association of neuropsychiatric symptoms in MCI with incident dementia and Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 21(seven): 685–95.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Apostolova, LG , Cummings, JL . Neuropsychiatric manifestations in balmy cerebral damage: a systematic review of the literature. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008; 25(2): 115–26.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Goossen, B , van der Starre, J , van der Heiden, C . A review of neuroimaging studies in generalized anxiety disorder: 'So where exercise we stand?'. J Neural Transm 2019; 126(9): 1203–sixteen.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Schaakxs, R , Comijs, HC , van der Mast, RC , Schoevers, RA , Beekman, AT , Penninx, BW . Risk factors for depression: differential across age? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017; 25(9): 966–77.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Penton-Voak, IS , Adams, S , Button, KS , Fluharty, M , Dalili, Chiliad , Browning, M , et al. Emotional recognition training modifies neural response to emotional faces but does not ameliorate mood in healthy volunteers with loftier levels of depressive symptoms. Psychol Med [Epub ahead of impress] 17 Feb 2020. Available from: https://doi.org/x.1017/S0033291719004124.Google Scholar

valentinodiany1971.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/bjpsych-open/article/emotion-processing-in-depression-and-anxiety-disorders-in-older-adults-systematic-review/2D1369911AA5F8135A451D67C4DEE651

0 Response to "Anxiety Disorders Are Emotional Older Adults Peer Reviewed Journal"

Post a Comment